When we think of the Texas Revolution, we usually focus on the period between February and April, 1836, but the revolution actually started much earlier.

When we think of the Texas Revolution, we usually focus on the period between February and April, 1836, but the revolution actually started much earlier.

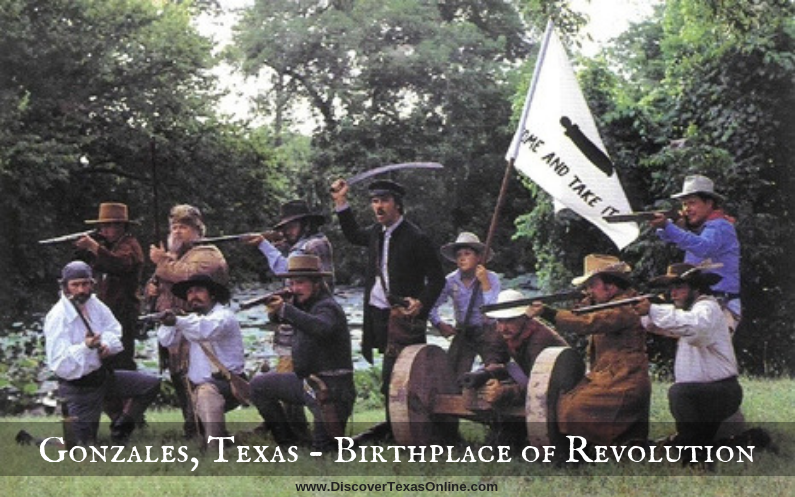

The Texas Revolution officially began in Gonzales, October 2, 1835.

The Battle of Gonzales on October 2, 1835 was a small skirmish, really. Only 18 men with a tiny cannon. Only one Mexican soldier was killed. But it only takes a spark to start a forest fire when the tinder is dry! Because Texans did not trust their government, the shots fired on that day in Gonzales started the Texas Revolution and earned Gonzales the nickname of “the Lexington of Texas.”

Here’s a short version of the story:

When Green DeWitt established his colony near the Guadalupe River in 1827, the colonists built a small fort to protect themselves from the Indians who had thwarted their first effort, but the raids continued. In 1831 DeWitt asked the Mexican government for a small cannon to protect the settlers against further attacks. His request was granted, though the cannon the colonists were given was “spiked”, meaning that a steel spike had been driven through the touch hole so that it could not be fired. The weapon was only meant to be a scare tactic.

When General Santa Anna tossed out the Mexican Constitution of 1824 and made himself dictator, one of his first moves was to disarm the citizens. He feared an armed militia might oppose him. The order to disarm was extremely unpopular, especially in northern Mexican states such as Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, and Coahuila y Tejas. In all, seven Mexican states resisted. Santa Anna’s troops squashed any signs of rebellion, but they were unprepared for the confrontation they met in Texas where many of the citizens were Anglo colonists who considered the right to keep and bear arms not only necessary and wise, but God-given.

When asked to relinquish their cannon, the citizens of Gonzales flatly refused. They buried the cannon in a peach orchard to hide it from 100 Mexican dragoons sent by the Texas military commander to retrieve it by force.

When the troops arrived at the Guadalupe River crossing on September 29th, they found the river flooded and the road blocked by 18 militiamen from Gonzales. They advised the Texans that they had orders for Alcalde (Mayor) Andrew Ponton and were told that he was “out of town.” The dragoons waited until October 1st, but it became clear that the Texans were buying time and gathering reinforcements, so the dragoons moved their camp up river to a place where they could more easily cross and pitched camp there.

But the Texans knew the land better. They headed up river as well, and on the morning of October 2 they attacked the Mexican encampment.

Castañeda, the Mexican commander, had orders not to engage in open conflict, so he fell back and sought a parlay with the Texans, asking why they had fired upon his men unprovoked.

The Texans replied that they would fight to keep their cannon (the local blacksmith had drilled out the spike so that it could be fired) and the Constitution of 1824. Perhaps they were surprised when Castañeda, himself, sympathized with their complaints. He was not in favor of Santa Anna’s federalist regime either, but as an officer he was obliged to follow orders.

When the Texans resumed fighting, Castañeda wisely followed the order to avoid open conflict. He retreated to Bexar (San Antonio) in hopes of avoiding a war…but it was too late. The fight for Texas liberty began that day at Gonzales.

Teaching Tip:

- Why do you think the men of Gonzales would fight for the right to keep a tiny, broken cannon?

- The town of Gonzales is small but well worth the trip! You can see the original “Come and Take It” cannon and flag in the Gonzales Memorial Museum…but don’t stop there! There’s LOTS to see and do in Gonzales, especially during their Come and Take It Celebration held each year to commemorate the Battle of Gonzales.