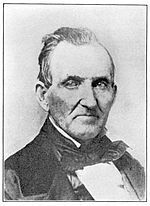

Lt. Col. James Clinton Neill

Born in North Carolina in 1790, Neill brought his wife and three children to Texas in 1831. He represented his district at the Convention of 1833 and joined the Texas militia as a captain of artillery.

He was in Gonzales the day the Mexican Army came reclaim the small cannon they’d given the town to defend itself against Indian attacks. When the Texians invited Col. Ugartechea’s men to “Come and Take It!” it was James Neill who, according to the eyewitness account of John Holland Jenkins, “fired the first gun for Texas at the beginning of the revolution.”

Neill also played a key role at the Alamo, where he begged for reinforcements and supplies to build up the defenses of the mission fort in December 1835. When James Bowie arrived on January 17 with orders to strip the artillery and blow up the fort, he was instead so impressed with Neill’s leadership that he became committed to the Alamo’s defense. Bowie wrote, “No other man in the army could have kept men at this post, under the neglect they have experienced.”

Neill had every intention of remaining in his post at the Alamo, but the winter of 1836 was wet and bitterly cold, and in mid-February word came that Neill’s family had been stricken with sickness. Appointing William B. Travis temporary commander, Neill left the Alamo to care for his family, promising to return within twenty days. Neill was on his way back to San Antonio, stopping by Gonzales where he purchased $90 worth of medical supplies for the garrison from his personal funds, when the Alamo fell on March 6.

Within the week he had joined Sam Houston’s army, and Houston made him commander of the artillery corps when the “Twin Sisters” arrived on April 11. Neill was in command of the Twin Sisters during the skirmish that preceded the Battle of San Jacinto on April 20th. His men turned back an enemy probe that could have revealed the position of the Texas army, but Neill’s hip was seriously wounded by grapeshot during the fighting.

Neill was granted a league of land in Harrisburg County for his service and a pension of $200 a year for life in compensation for his injuries, but he is another Texas hero for whom no town or county is named.