Samuel May Williams did not come to Texas to become an empresario, but he became one nonetheless…and was one of the most wealthy and successful of the Texas empresarios.

Samuel May Williams was born on October 4, 1795 in Providence, Rhode Island. His father was a sea captain. Samuel was educated in Providence and then, at 15, was apprenticed to his uncle, who was commission merchant. He did well and was eventually appointed to act as supercargo (a representative of the ship’s owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale) on a voyage to Buenos Aires. He stayed on in South America for some time, mastering Spanish and learning Latin American business practices.

By the time he was 24, he had settled in New Orleans. This was in 1819 when Stephen F. Austin was also in New Orleans pursuing a degree in law. Perhaps it was at this time that the two young men from wealthy families met?

Austin left for Texas in his father’s stead in 1821. Williams left for Texas in 1822. For some reason he chose to travel in cognito as “E. Eccleston”, but he resumed his identity in 1823 when Austin hired him as translator and clerk for his colony at San Felipe.

Williams served as Austin’s lieutenant for 13 years–writing deeds, keeping records, and directing colonial activities during Austin’s absences–until the start of the Texas Revolution.

In addition, Williams served in several other posts. He was named postmaster of San Felipe in 1826. In 1827 the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas appointed him revenue collector and dispenser of stamped paper. And in 1828 he became secretary to the ayuntamiento (town council) of San Felipe. This last post was very important, because the government paid Williams for his service in land–11 leagues (49,000 acres) of land, and Williams got to select the location. As a ship captain’s son and former shipping merchant, he chose his land along the strategic waterways around Oyster Creek and Buffalo Bayou, in the area where Houston, Baytown, Galveston, and Freeport lie today. Now Samuel May Williams was an empresario.

One other business venture in which he participated was to partner with Thomas McKinney to open a commission house–a brokerage firm that buys and sells contracts for merchants based on their estimated future value. Williams used credit from his family’s mercantile contacts to fund the business. It was a calculated risk, and in return Williams and McKinney charged a commission on transactions made on their customers’ behalf. From their headquarters at Quintana near the mouth of the Brazos River, McKinney and Williams dominated the Brazos cotton trade.

As Mexican President Santa Anna grabbed more and more power and made the colonists’ lives more and more difficult, Williams attended a meeting in Monclova in 1835 where the Coahuila state legislature planned to sell grants of land to raise funds to oppose the dictator. Williams contracted for two grants of 400 leagues. This earned him notoriety as a revolutionary. Williams fled to the US to escape arrest, but he did not stop supporting the Texians’ cause. His firm used its credit in the US to purchase arms and raise $99,000 (over $2.675 million in today’s dollars) for the Texas Revolution. The revolution was successful, but Williams and McKinney were never fully repaid. After the war, they moved their company to Galveston in 1838. Still actively involved on behalf of the Texas Republic, Williams was commissioned to negotiate a $5 million loan in the US to purchase seven ships for the Texas Navy.

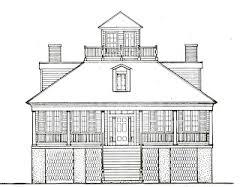

Soon after, though, Williams and his wife settled in their new Galveston home, which still stands. The raised Creole cottage has the unusual addition of a captains walk (or cupola) on top from which Williams might watch the sea–a tribute to both his New Orleans and Rhode Island roots.

If you visit his home today, you may notice that the basement level is no longer a full story high. This is because the residents of Galveston raised the sea level of the island several feet following the disastrous hurricane of 1900.